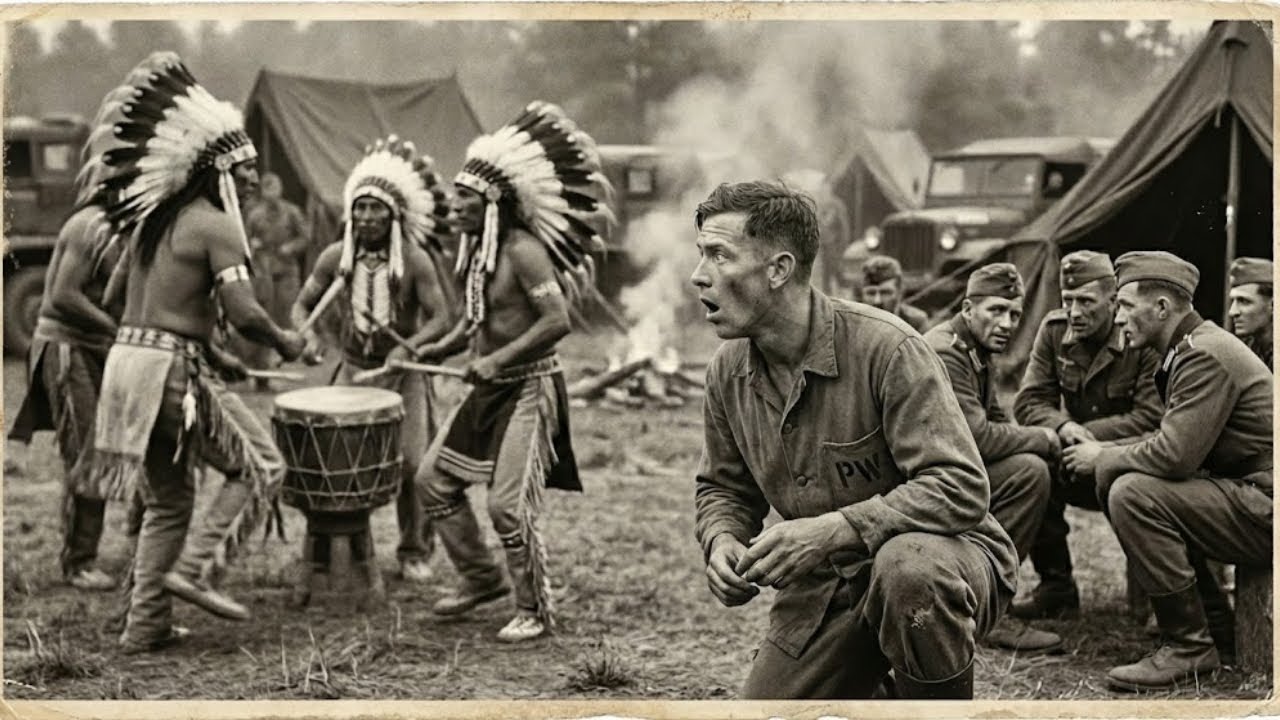

German POWs in Oklahoma Were Shocked to be Taken to a Native American Powwow

August 10th, 1944. Camp Gruber, Oklahoma. The drum beat rolled across the prairie like thunder from another world. German prisoners stood frozen along the fence line, cigarettes forgotten between their fingers. The sound came from beyond the wire, deep and rhythmic, rising from the red earth itself.

They had been told to expect a demonstration. What they witnessed instead would shatter everything they’d been taught to believe. Before we continue, if you’re enjoying this story, hit that like button and subscribe so you never miss these untold chapters of history. Drop a comment telling us where you’re watching from.

Now, back to that August afternoon when reality collided with Nazi propaganda in the most unexpected way. The prisoners watched as figures emerged from the treeine, wearing colors that seemed to burn against the dusty landscape. Eagle feathers caught the dying light. Beadwork glittered on leather vests, and among the dancers, unmistakable in their olive drab uniforms were United States Army soldiers, not conquered people, not museum exhibits brought to life.

Warriors, living, breathing proof that everything the Reich had taught them was a lie. By the summer of 1944, more than 370,000 German prisoners of war were scattered across American soil. They occupied over 500 camps in 46 states, from Texas cotton fields to Michigan lumber mills. The War Department hadn’t anticipated this volume.

These men had surrendered in Tunisia, Sicily, and the Italian campaigns. They arrived expecting brutal treatment, perhaps execution. Instead, they found themselves in places like Camp Gruber, sprawled across 63,000 acres of Oklahoma hills. The landscape was beautiful in a way that confused them post oak forests.

Limestone bluffs glowing pink at sunset, spring-fed creeks carving ancient valleys. The camp itself followed standard military precision. Rows of wooden barracks surrounded by chainlink fencing and barbed wire. Guard towers at regular intervals. a mess hall serving meals that matched American enlisted men’s rations by Geneva Convention requirement.

This fact alone shocked many prisoners who expected deliberate starvation. Daily life unfolded with clockwork regularity. Really at 0530, roll call at 060. Work details occupied the daylight hours. Agricultural labor, road maintenance, forestry operations. Prisoners received 80 cents daily in camp script for the canteen.

But beneath this routine structure, something deeper festered. These men carried the accumulated weight of systematic indoctrination. Years of propaganda films, Hitler youth education, vermocked training manuals presenting racial hierarchy as scientific fact. They’d been taught that the German folk represented evolution’s pinnacle, that Slavic peoples were subhuman, that Jews required biological elimination, and crucially, that America’s native peoples no longer existed. This wasn’t casual assumption.

It was central to Nazi ideology. Joseph Gobles’s propaganda ministry produced detailed materials arguing that America had achieved racial purification through systematic extermination. German school children studied maps showing vanished tribes. Veract soldiers received briefings explaining that westward expansion demonstrated the practical viability of lean living space conquered through removal of inferior peoples.

The lie was comprehensive embedded so deeply that questioning never occurred. Carl Weisner a prisoner from Hamburg later described their indoctrination in letters home. They’d watched films showing empty prairies, read accounts of America’s successful elimination campaign. The message was clear and repeated.

Indigenous peoples were extinct. Proof that racial hierarchy could be enforced through will and violence. For prisoners at Camp Gruber, this remained unexamined truth until that August afternoon when the drums began. The idea came from Captain Thomas Willleum, a white-ear chipoa from Minnesota. One of approximately 550 Native American officers serving in the US Army during the war.

Assigned to Camp Gruber as special liaison officer in early 1944, he brought perspective the standard re-education materials couldn’t provide. He understood what the prisoners didn’t know. More importantly, he understood what pamphlets and films could never adequately convey. In a memorandum to Colonel Marcus Ray dated June 12th, 1944, Willleam wrote with unusual clarity, “You can show them printed materials.

You can screen approved motion pictures. You can lecture until your voice gives out, but they will not believe what they merely read or hear. They must see with their own eyes. They must witness what cannot be denied.” Willum proposed bringing Native American soldiers from nearby installations along with civilian elders from the Cherokee and Muscogee Creek nations.

The event would serve multiple purposes, morale boost for native servicemen, cultural education for Germans. And though Willom didn’t state it explicitly, a direct undeniable repudiation of Nazi racial propaganda, Colonel Ray approved the proposal on June 28th. Preparations began immediately. The logistics proved complex.

Elders from the Cherokee community in Talika agreed to participate. Cultural representatives from the Muscogee Creek Nation in Okmogi joined them. Native American soldiers stationed at Camp Gruber and nearby Fort Sil requested special leave. A parade ground near the main entrance was cleared and prepared. Wooden benches arranged in rising rows.

On August 12th, prisoners assembled at 1600 hours under hazy skies. They’d been told only that they would witness an American cultural event. Military guards escorted them in orderly groups of 50. Most expected something resembling military review, perhaps a brass band, flag ceremony, speeches.

What they encountered defied every mental category they possessed. The opening drum call began without formal announcement. It rose from a group of elders seated in the cleared ground, weathered hands moving in precise unison against a large ceremonial drum stretched with buffalo hide. The sound was entirely unlike European marshall tradition, not a march, not a military cadence, a pulse that seemed to emanate from the earth itself. Then the dancers emerged.

They came from the treeine in slow dignified procession. Men in full traditional regalia, women in jingle dresses that chimed with each step, children carrying small fans crafted from eagle feathers. Among them walked soldiers wearing standard army fatigues, uniforms unadorned except for unit insignia and service ribbons.

As the drum beat accelerated, these soldiers joined the traditional dancers. Military bearing blended seamlessly with ancestral movement patterns. A photograph exists in the Oklahoma Historical Society archives. Carefully preserved under catalog number 20,457. It shows German pose seated on rough wooden bleachers.

Faces turned toward something beyond the camera’s frame. Most appear young, early 20s or younger boys who became soldiers. Soldiers who became prisoners. Their expressions are difficult to categorize. Some look confused, brows furrowed in concentration. Others seem almost frightened, witnessing something that violated natural order.

One man in the front row has removed his cap, holding it pressed against his chest. The photograph’s label reads simply, “German post attending Native American cultural demonstration, Camp Gruber, Oklahoma, August 1944.” The word demonstration again so inadequate. What the camera captured was something far more dangerous to men raised on carefully constructed lies.

Weisner later described the moment in letters. We did not understand what we were seeing. These were Indians, real Indians living and breathing, not figures from American cinema. And they were soldiers. American soldiers wearing the same uniform as our guards. Some displayed combat medals. One had a bandaged arm and a sling, a wound from battle.

They danced as though the ground beneath them belonged to them, as though it always had and always would. The demonstration continued nearly 2 hours. It included traditional war dances, honor songs dating back generations, a veterans recognition ceremony during which Cherokee elders presented sacred eagle feathers to young soldiers preparing to deploy overseas.

An army chaplain offered brief explanations through a German-speaking transl, but many prisoners found the visual spectacle far more compelling than any words. At approximately 1730 hours, something unscripted occurred. What walking stick? The Cherokee elder, who had led the opening ceremonies, walked slowly toward the fence line.

He was 73 years old that summer, hair white as cloud, back unbounded despite decades of weight. His grandfather had survived the Trail of Tears. His sons were fighting in the Pacific theater. Through the translator, he asked if any prisoners wished to pose questions. For a long moment, absolute silence hung in the humid air.

Then a young prisoner near the front, later identified as a former university student from Leipig, raised his hand tentatively. “We were taught your people had been destroyed,” he said quietly. that America eliminated you the same way they wish to eliminate us. Is this teaching not correct? The translator conveyed the question carefully, word by word.

Walking stick considered for what seemed a very long time. The drums had fallen silent. Even the cicas seemed to pause. I am standing before you, the elder finally replied. My father survived the Trail of Tears when he was a small child. His father fought against Andrew Jackson’s armies. We have endured everything meant to destroy us. We remain here.

We will remain here when your war becomes distant history. We will remain here when the lies you were taught are completely forgotten. The translatter hesitated, then delivered the response precisely. No one spoke afterward. The drums gradually resumed their ancient rhythm. The dancing continued as twilight approached.

But something fundamental had shifted. In the humid Oklahoma atmosphere, a weight previously invisible became suddenly, undeniably apparent. A camp intelligence report filed 3 days later documented an unusual pattern. Dramatically increased requests for books about American history, particularly regarding Native American treaties and reservation policies.

The camp library, previously seeing minimal activity, reported unprecedented demand for limited anthropology holdings. The questions had begun. They would not stop. September rains came without warning. They swept across eastern Oklahoma and heavy sheets, transforming red dirt roads into rivers of rustcoled mud.

The pow-wow gatherings concluded for the season, but their effects lingered in ways both measurable and mysterious, rippling outward like stones dropped in still water. Camp intelligence reports from late 1944 documented gradual but unmistakable softening among the general prisoner population. Attendance at voluntary education programs, American history lectures, English instruction, moderated discussion groups exploring democratic principles increased by nearly 40% within weeks.

Requests for transfer to the cooperative compound where prisoners who formally renounced Nazi ideology received additional privileges rose correspondingly. The camp library ordered additional books. discussion groups formed spontaneously in barracks after lights out. Not everyone changed, of course.

History rarely grants such clean resolutions. Some men remained stubbornly committed to beliefs they’d carried across the ocean. They wrote defiant letters home, declaring faith and eventual German victory. They sang vermach marching songs in their barracks after curfew, voices rising in darkness. They whispered about the final triumph propaganda still promised.

But that triumph never came. May 8th, 1945. Victory in Europe Day. The news arrived at Camp Gruber by Armed Forces Radio. Confirmed by camp commanders and brief announcement during morning roll call. The European war was finished. Germany had surrendered unconditionally. The thousand-year Reich had lasted exactly 12 years.

Henrik Brandt, originally captured in Tunisia during spring 1943, later recalled that moment in an interview recorded by German public television in 1995. We stood in formation as we did every morning, and the American officer told us quite simply that the Reich had fallen. Some men around me wept openly. Others stood rigid as statues, unable to process what they’d heard.

And I found myself thinking of the Indians dancing. I thought they were right all along. They remained standing. They survived everything. And what we believed, the lies that shaped our understanding, that was what had truly been destroyed. Repatriation began in late 1945 and continued methodically through 1946. Prisoners were processed in scheduled waves, loaded onto ships, transported back across the Atlantic to a Germany they could scarcely recognize.

Great cities bombed to rubble, families scattered across occupation zones. The entire elaborate structure of the Reich reduced to ashes and bitter memory. What they carried home proved difficult to measure. Researchers in subsequent decades documented that some camp grouper prisoners became active participants in West Germany’s postwar democratic reconstruction.

A handful entered politics, education, journalism, civil service. Their American captivity experiences, including the strange interlude of the Oklahoma pow-wows, shaped their evolving understanding of race, nation, and the elaborate lies governments construct for their citizens. Captain Thomas Willleum returned to the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota after the war.

He worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs until retirement in 1968, spending decades advocating for tribal sovereignty and cultural preservation. He rarely spoke publicly about the Camp Gruber Pow-Wow program, but he maintained a folder of letters from former German prisoners who wrote years later to express gratitude.

Those letters remained in his family’s possession until formally donated to the Minnesota Historical Society in 2004. What walking stick passed away in 1952 in Taliqua on the same land his family had cultivated since surviving the Trail of Tears more than a century earlier. His descendants maintained the tradition of pow-wow dancing through subsequent generations.

His greatgrandson served two combat deployments in Iraq. Camp Gruber itself transitioned back to training facility status after the war concluded. It remains operational today as a National Guard installation spread across the same cooks and hills where prisoners once watched elders dance against the setting sun.

The original barracks are gone. The perimeter wire has long since been removed, but the land holds its memories. In 2019, the Oklahoma Historical Society mounted a modest exhibition titled Enemies and Allies Pose in Oklahoma during World War II. It included several photographs from Camp Gruber, including that singular image of German prisoners witnessing the pow-wow catalog number 20,457.

Visitors of all ages paused before it. Some stood in contemplative silence. Others openly wept. A descendant of one of the Cherokee dancers attended the exhibition opening. She spoke briefly about what those wartime pow-wows had meant to her community. a chance to demonstrate strength, to embody survival, to look their capttors directly in the eyes, and communicate without requiring translation.

“We are still here,” a reporter asked whether she believed the prisoners had truly understood. She considered the question carefully before answering. “Some did,” she said finally. “Some never could. That’s always how these things work. The Oklahoma summer arrives each August, bringing the same heavy heat that once pressed down on Camp Gruber 80 years ago.

The sun still settles low and merciless over the hills, leeching the grass to a brittle yellow, and pulling the moisture from the air until every breath feels earned. Cicas still drone their ancient songs in the blackjack oaks, rising and falling like a living tide. Red dust still lifts in clouds when trucks rumble down country roads, clinging to skin and clothing, settling into the creases of memory.

Time moves forward, but the land remembers. The land always remembers. In the quiet places, if you listen closely, the past does not feel distinct. It lingers in the heat shimmer above the fields, in the slow bend of creeks that have seen too much, in the soil that has carried footsteps from one generation to the next.

Camp Gruber itself has long since shed its wartime purpose. Its barracks and fences reduced to fragments and impressions. What was once razor wire and wooden towers has been reclaimed by weeds, by weather, by the patient work of years. The war that justified it has faded into history’s long afternoon, softened by textbooks and distance.

Names have slipped from public memory, dates blur, photographs yellow. The prisoners have passed now. The guards have passed. The officers, the bureaucrats, the men who signed papers and enforced rules, all gone. Their lives closed out quietly, folded into family stories, or forgotten entirely. The suffering that unfolded behind the wire rarely appears in monuments or official commemorations.

There are no parades for it, no easy narratives. And yet absence does not mean eraser. Because somewhere beyond the former perimeter, beyond the abandoned foundations and the overgrown roads, the drums still beat. They beat at pow-wows in Taliqua and Akmalgi, in Tulsa and Oklahoma City, and in communities scattered across the state.

They beat in school gyms and fairgrounds, under open skies and canvas shelters. They beat in circles where elders sit beside children, where dancers step forward carrying stories in their bodies. The rhythm rolls outward, steady and insistent, echoing across time and space. They beat for ancestors who endured the trail of tears who walked west under armed watch, leaving graves along the road and prayers in the dust.

They beat for those who survived removal, aotment, broken treaties, and the relentless pressure to disappear. They beat for warriors who fought and died on foreign battlefields, wearing uniforms of a nation that had once declared them expendable. They beat for prisoners whose names were changed, whose language was forbidden, whose loyalty was questioned, and whose suffering was buried beneath classified files and official silence.

They beat for truth that no propaganda ministry could ever erase. The drums do not speak in headlines or speeches. They do not argue or persuade. They remember. They carry forward what was never meant to survive. Each strike of hide against wood is an act of continuity, a refusal to be erased by time, policy, or neglect.

The rhythms are older than any written language, older than borders on maps, older than the idea that history belongs only to the victors. They come from peoples who were told again and again that they would not last, that they would be absorbed, broken, or forgotten. and who endured anyway. In the face of imprisonment, they endured.

In the face of exile, they endured. In the face of war, suspicion, and loss, they endured. Survival did not come clean or easy. It came scarred and complicated, shaped by grief, and resilience in equal measure. Yet it came generation after generation carried something forward, even when carrying it meant doing so quietly in private in defiance of the world’s expectations.

Oklahoma summers return. Heat presses, cicas sing, dust rises, drums keep sounding, history speaking beyond fallen fences and towers. Living in memory, rhythm, endurance. War faded. Camp vanished.