They Mocked His ‘Mail-Order’ Rifle — Until He Killed 11 Japanese Snipers in 4 Days

At 9:17 on the morning of January 22nd, 1943, Second Lieutenant John George settled into the ruins of a Japanese bunker on Guadal Canal’s western perimeter, 240 yd from a grove of banyan trees that had killed 14 Americans in 72 hours. He was 27 years old. Illinois state rifle champion, zero combat kills.

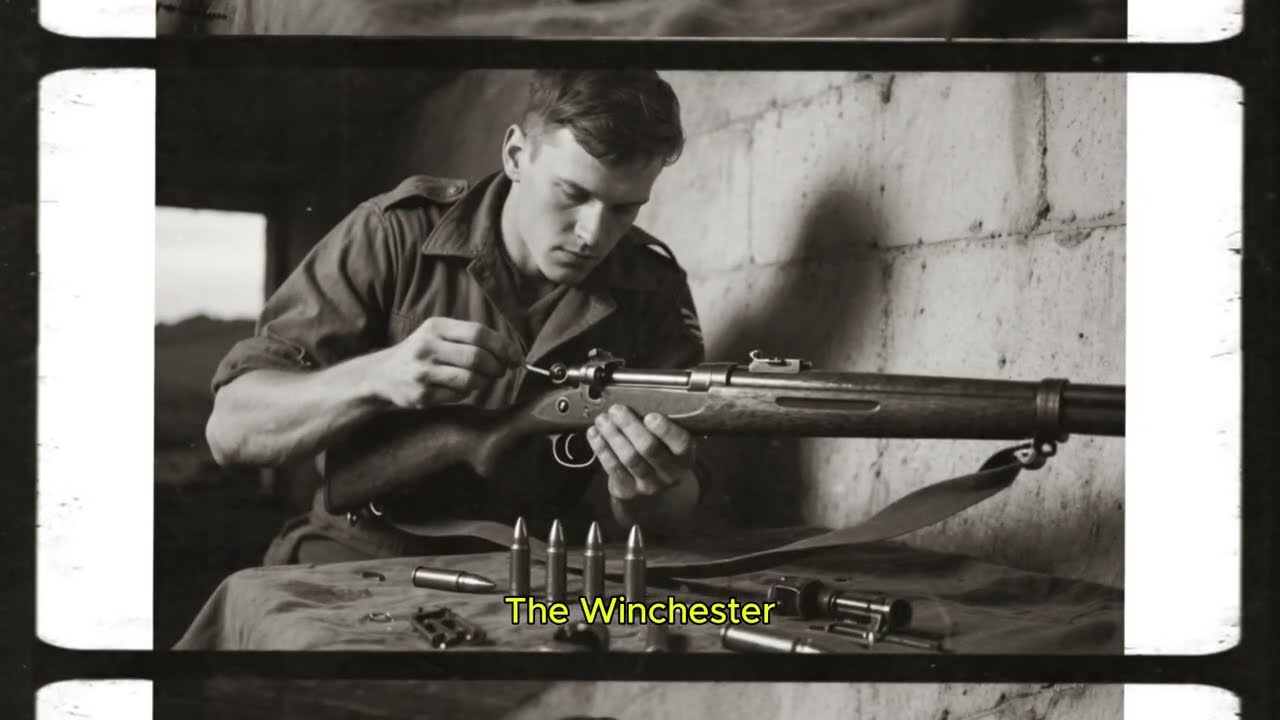

The Winchester Model 70 resting against the sandbags beside him had cost two years of National Guard pay. The Lyman Alaskan scope mounted on top had been mocked by every officer in his battalion since it arrived 6 weeks late in a crate marked fragile. His company commander had called it a male order sweetheart.

The battalion armorer wanted to know if George planned to hunt deer or fight a war. George had explained it was for the Japanese. Then he waited six weeks for a chance to prove it. The 132nd Infantry Regiment had relieved the Marine garrison in late December. The Marines had held Henderson Field since August, but they had not taken the high ground.

Mount Austin, 1,400 ft of Japanese fortified ridge line anchored the Western Defense. George’s battalion assaulted it on December 17th. 16 days of close fighting through interconnected bunkers. 34 men killed, 279 wounded. When they finally secured the western slope on January 2nd, George had not fired his rifle once.

The terrain did not allow it. Engagement ranges inside the jungle canopy rarely exceeded 50 yards. Scoped rifles were useless in vegetation, so dense you identified targets by sound before sight. The coastal groves west of Point Cruise were different. Open enough for long sight lines, dense enough for concealment.

The Japanese soldiers who had withdrawn from Henderson Field were using the area as a staging point for evacuation. Some of those soldiers were trained snipers with scoped Arisaka type 98 rifles. Between January 19th and 21st, they killed 14 Americans. Corporal Davis died filling cantens at a creek.

Two men from L company were shot during patrol. A third was hit through the neck from a tree. His squad had passed twice. Battalion command summoned George on the evening of January 21st. The snipers were triting his force faster than disease. George explained his credentials. Illinois state championship at 1,000 yd 1939.

6-in groups at 600 yardds with iron sights with the lineman Alaskan five rounds inside 4 in at 300. The commander gave him until morning. George spent the night verifying his rifle. The Winchester had been packed in cosmoline for the Pacific crossing. He field stripped it, cleaned each component, checked the scope mounts, loaded five rounds of306 hunting ammunition.

At first light, he moved into the captured bunker overlooking the groves. No spotter, no radio, just a rifle and 60 rounds and stripper clips. The Lman Alaskan offered two and a half power magnification, enough to see movement in the canopy that the naked eye would miss. George glassed the trees methodically. At 917, he found it.

A branch shifted 87 ft up in a banyan tree. No breeze. The branch moved again. Then he saw the shape. A man in dark clothing positioned in a fork where three limbs met, facing east toward the American supply trail. George adjusted his scope two clicks right for wind. The Winchester’s trigger broke clean at 3 and 12 lb. He fired.

The recoil pushed into his shoulder. Across 240 yd of humid air, the Japanese sniper jerked and fell. His body tumbled 90 ft through the branches and hit the ground. George worked the bolt, chambered a fresh round, and kept his scope on the tree. Japanese snipers worked in pairs. At 9:43, he found the second man.

Different tree 60 yd north, descending after hearing the shot. George led the movement and fired. The second sniper fell backward off the trunk. Two shots, two kills. George reloaded from a stripper clip. At 11:21, a Japanese bullet struck the sandbag 6 in from his head. Dirt sprayed across his face.

George rolled left and waited 3 minutes. The shot had come from the southwest. He glassed the trees slowly. At 11:38, he found the shooter. Third tree and a cluster of five banyions 73 ft up. The sniper had moved to a different branch but remained in the same tree. George fired. The third man fell without sound.

By noon, George had killed five Japanese snipers. Word traveled through the battalion. Men who had called his rifle a toy now asked to watch him work. George refused. Spectators drew attention. The Japanese adapted after the fifth kill. They stopped moving during daylight. George spent the afternoon watching motionless trees.

At 1600, he returned to headquarters. Captain Morris was waiting. The mockery had left his voice. He wanted George back in position at dawn. January 23rd began with rain that reduced visibility and turned the jungle floor to mud. George sat in the bunker until 8:15 when the weather cleared.

He spotted the first sniper at 9:12. The soldier had climbed into position during the rain when sound was masked. This sniper had chosen a tree 290 yd out. Longer range than the previous day. They were learning his capabilities. George compensated and fired. The sixth man fell. At 957, Japanese mortar began impacting around the bunker.

They had triangulated his position. George grabbed his rifle and ran, diving into a shell crater. As the third salvo obliterated the bunker, he relocated to a fallen tree 120 yards north. The Japanese were now hunting him as actively as he hunted them. At 1423, George killed his seventh sniper. At 1541, he killed his eighth.

This one had climbed to 94 ft. Good concealment until the sun angle created a silhouette. At 1700, Morris sent a runner. George reported eight confirmed kills over two days. 12 rounds fired, eight hits. Morris assigned him to continue at dawn on January 24th. That night, George considered the mathematics.

Intelligence reported 11 Japanese snipers. Eight were dead. Three remained. Those three would be the most experienced. And now they knew exactly what George looked like and what rifle he carried. The rain started again at 4:15, delaying operations. George used the time to move to a new position, a cluster of rocks the Marines had used as a machine gun nest, elevated, good cover, overlapping fields of fire.

At 8:17 on January 24th, George found sniper number 9, palm tree 190 yd out, low position, only 40 ft up. unusual. The palm frrons created a natural hide, but George’s elevated angle gave him a view down into the fronds. He aimed, began trigger squeeze, then stopped. The position was too obvious. The remaining snipers would not make elementary mistakes unless it was bait.

George scanned the surrounding trees. At 8:28, he found the real threat. Banyan tree, 80 yd northwest, 91 ft up. perfect hide with clear line of sight to George’s previous position. The sniper was waiting for George to take the bait. George decided to use the bait against them. He aimed at the decoy in the palm and fired. The decoy fell.

George immediately swung toward the banyan. The real sniper would react. George saw the movement as the sniper repositioned. George fired before the turn completed. The real sniper fell. Two shots. Two kills, but George had revealed his position. He grabbed his rifle and ran, dropping into a drainage ditch.

At 8:34, Japanese machine gun fire raked the rocks where he had been positioned. George relocated to a water-filled crater 100 yd east. 10 confirmed kills, one remaining. At 9:47, George realized his mistake. The 11th sniper was not in the trees. He was on the ground crawling toward George’s last position.

At 10:03, the Japanese sniper reached the rocks and took position facing east. 38 yd from George’s actual position, but facing the wrong direction, George hesitated. This sniper had survived 10 days. The position was too exposed. This had to be bait. At 10:06, George found the second soldier 70 yard northwest behind a fallen tree.

two men working together. At 10:13, both Japanese soldiers stood and began moving east in a coordinated sweep. George remained motionless in the water. The soldiers moved past his crater, backs exposed. George rose from the water, aimed at the closer soldier, and fired. The man dropped.

George worked the bolt, swung toward the second soldier who was turning. George fired first. The second soldier fell. 11 shots over three days. 11 Japanese snipers dead. As George climbed from the crater, he heard voices. Japanese voices from the treeine. Multiple men moving toward the fallen soldiers.

Infantry, a recovery team. George dropped back into the crater and submerged. The voices grew closer. They had found his tracks. At 10:31, a Japanese soldier appeared at the crater rim, looking directly at George. George fired from the water. The soldier fell. Two more soldiers appeared. George fired twice. Both dropped. Three rounds left.

More soldiers approaching. George climbed from the crater and ran north. Japanese fire followed. Bullets snapped past struck trees. George ran 90 seconds before diving into another crater. The voices were distant. They had not pursued, regrouping around their dead, George checked his rifle. Mud on the stock, water dripping from the barrel.

Two rounds remaining. At 113, George reached the American perimeter and reported to Captain Morris. 11 Japanese snipers killed over 4 days. 12 rounds fired against snipers, 11 hits. Then a firefight with infantry. Three more kills. At 1400, word came from division headquarters.

The regimental commander wanted to see George. Colonel Ferry had one question. Could George train other men to do what he had done? Ferry said division had 14 Springfield rifles with unert scopes left by Marines. Ferry had 40 men qualified as expert marksmen. Ferry wanted George to create a sniper section.

George accepted with one condition. He wanted to keep his Winchester. Ferry approved. Training began January 27th. George started with fundamentals. Breathing control, triggered discipline, reading wind. By January 30th, 32 of 40 men could consistently hit man-sized targets at 300 yd. George divided them into 16 twoman teams, shooter and spotter.

On February 1st, George took four teams into the field to clear Japanese positions west of the Matanekal River. 23 Japanese soldiers killed that day. Zero American casualties. The sniper section continued operations through early February. By February 9th, 74 confirmed kills. On February 7th, a Japanese rifleman shot George in the left shoulder.

The wound was serious, but not fatal. George was evacuated to the field hospital. During his recovery, the Japanese completed their evacuation. The campaign was over. George’s sniper section had operated 12 days. 74 confirmed kills, zero friendly casualties during sniper operations. Colonel Ferry recommended George for Bronze Star.

While George recovered, orders came from Pacific Command, Burma classified. George volunteered. By March, George was on a transport west. His Winchester packed in a waterproof case. The transport reached India on April 3rd. George and 200 other officers were briefed. They would join a new unit, 3,000 men. The men called themselves Merrill’s Marauders.

Training began in April. Long range penetration tactics, jungle survival, operations without supply lines. George modified his equipment for Burma. He replaced the Lyman Alaskan with a lighter Weaver 330 and switched to a synthetic stock, reduced rifle weight from 9 lb 12 oz to 8 lb 14 oz.

The Marauders entered Burma February 1944. Mission capture Muccina airfield. The Marauders would approach through terrain the Japanese considered impassible. George’s battalion began the march February 24th. By March, they had covered 217 mi and engaged Japanese forces 12 times. George used his Winchester three times during the march.

Three shots, three kills. George never fired more than once per engagement. One shot announced presence. A second gave the Japanese time to locate him. The march took 3 months. By late May, marauders had covered over 700 m, losing more men to disease than combat. On May 17th, marauders captured Mutina airfield.

The operation succeeded, but the unit was combat ineffective. George survived Burma. His Winchester survived, but the rifle was used only seven times in 3 months. Most combat was close ambush, where scoped rifles offered no advantage. George realized something during those three months that stayed with him long after the humidity of Burma had faded from his bones.

The Winchester Model 70 was an exceptional rifle, perhaps the finest boltaction sporting rifle ever built. It was accurate, reliable, and honest in a way machinery rarely is, but mode rn warfare was already changing around it. Firepower was becoming collective rather than individual.

rn warfare was already changing around it. Firepower was becoming collective rather than individual.

Semi-automatic rifles were no longer novelties. They were becoming standard issue. The future belonged to volume of fire, coordination, and speed, not patience, and a single well-placed shot. By June of 1944, George was evacuated from Burma. His body worn thin by disease and exhaustion. The small improvised unit he had worked with dissolved quietly without ceremony.

Men were reassigned, paperwork completed, equipment inventoried and forgotten. George himself was sent back to the United States, no longer as a combat officer, but as an instructor. He trained new soldiers, men who would carry rifles he had never used, and fight wars that would look nothing like the ones he had survived.

He never fired his Winchester in combat again. When George was discharged in January of 1947, he held the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. His service record was immaculate and brief in its official language. Two bronze stars, one purple heart combat infantry badge. Lines of ink that failed to convey the reality of Guadal Canal or the long lonely days in the jungle.

He returned to Illinois older than his years, disciplined, reserved, and unwilling to romanticize what he had done. He enrolled at Princeton under the GI Bill, and graduated with highest honors in 1,950. From there, he spent four years at Oxford, followed by four more in British East Africa, studying languages, cultures, and political systems with the same methodical attention he had once given wind and distance.

Eventually, George joined the State Department’s Foreign Affairs Institute as a consultant on African affairs. His career was quiet, effective, and largely anonymous. He advised, wrote reports, and traveled extensively. He never spoke publicly about Guadal Canal or Burma. When asked, he redirected the conversation or offered something deliberately bland.

Those experiences were not stories to him. They were data points, lessons learned at great cost. In 1947, shortly after his discharge, George made a private decision. He would write down what had happened, not for publication, not for recognition, but simply to create a record while memory was still precise.

He wrote every day for 6 months, working carefully, reconstructing events shot by shot, mistake by mistake. The manuscript grew steadily until it exceeded 400 pages. It was spare, analytical, almost clinical in tone. There were no dramatic flourishes, no attempts at self- mythology, just observation and outcome. A friend who read the manuscript, someone connected to the National Rifle Association, recognized its value and suggested publication.

George hesitated, then agreed on the condition that nothing be sensationalized. The book was published in 1947 under the title Shots Fired in Anger. It found an audience immediately among firearms enthusiasts and military professionals. Historians noted its precision. Shooters admired its honesty.

It became quietly a classic. Decades later, it would still be in print, unchanged, its relevance unddeinished by time. George lived long enough to watch three more wars unfold. Korea, Vietnam, the Gulf War. He observed the evolution of the military rifle from the M1 Garand to the M14 and then the M16.

He watched sniping transform from an improvised role filled by talented individuals into a formalized military specialty with doctrine, schools, and standardized equipment. The skills he had relied upon, self-taught, field adapted, personal, were now institutionalized, and in many ways improved. The lone rifleman gave way to the team.

John George died on January 3rd, 2009. He was 90 years old. His death passed quietly, noted in brief obituaries that summarized his life in the language of service records and academic appointments. Afterward, the Winchester Model 70 was donated to the National Firearms Museum in Fairfax, Virginia. It rests there now in a climate control display case, woodpished, steel blued, carefully preserved.

Most visitors walk past it without stopping. It does not draw attention. It looks like any other mid-century sporting rifle, well-made, traditional, unremarkable. To the casual eye, it is indistinguishable from thousands of similar rifles produced in the same era. But it is not just another rifle.

It is the rifle that proved a state champion marksman armed with a male order scope and no formal sniper school could outshoot professionally trained military snipers. The rifle that helped clear point crews in 4 days when an entire battalion supported by artillery and air power had failed to do so.

The rifle that demonstrated what discipline, patience, and individual judgment could achieve when doctrine offered no solutions and firepower alone was insufficient. It was never intended to be a symbol. It was simply a tool selected because it worked, carried because it could be trusted. Its success was not the result of innovation or technology, but a skill applied under pressure.

The rifle did exactly what it was designed to do, nothing more. And now it sits behind glass, largely unnoticed, a relic, not because it failed, not because it was replaced by something better in every respect, but because the nature of war moved past it. Modern battlefields demand different tools, different systems, different answers.

The skills that once made the rifle decisive became less central as warfare evolved. The rifle did not change. The battlefield did.